April 28, Day 12 (2). Madrid. Prado Museum and Reina Sofia.

See Travel Itinerary for a rationale of this trip, a who’s who of those travelling.

We were fairly early at the Prado and the queue was short. Once inside, we went through a screening process and left our backpacks at a central depository.

There is no way we could do justice to the collection in the few hours we had planned, so we made some ruthless choices, looking mainly at paintings by El Greco (1541-1614), Diego Velázquez de Silva(1599-1660) and Francisco de Goya (1746-1828).

Although Margaret and I had been several times to the Prado, it was still a bewildering experience, even with a floor plan, to get our bearings. Getting a little lost did mean, however, that we could admire paintings by other European artists.

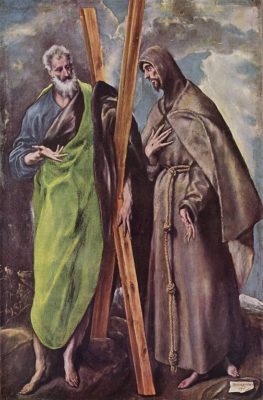

After a while, we found our way to the El Greco rooms. El Greco was actually born on the island of Crete, but his Greek name (Domenicos Theotocopoulos) led to El Greco: the Greek. He arrived in Spain around 1577, after stops in Venice and Rome, and settled in Toledo, Spain’s spiritual heart. It was here where he produced his most famous paintings, many intended as altar pieces commissioned by the church or church dignitaries.

El Greco’s paintings are amongst the most easily recognisable in the world of art.

If El Greco is the painter of Spain’s religious fervour in the second half of the 16th century, Velázquez is his secular equivalent in the first half of the 17th century. Born in Seville in 1599, Velázquez was established in Madrid in 1623, having won the attention of Spain’s most powerful minister to the king, and fellow Sevillian, the Count-Duke of Olivares. In the same year, Velázquez painted a portrait of the king. The portrait pleased the king, and by the end of 1623, Velázquez was confirmed as court painter.

Although the Prado has the largest collection of Velázquez’s paintings, we decided to concentrate on just four: Las Meninas (Maids of Honour 1656), La Rendición de Breda (The Surrender of Breda, before 1635), Las Hilanderas (The Tapestry Weavers /Spinners or Fable of Arachne 1657), and Los borrachos (The Drinkers/ Topers/Bacchus 1628).

Velázquez has been called a “painter’s painter,” i.e. the consummate artist, and in a poll of art experts held by the Illustrated London News in August 1985 his painting Maids of Honour was voted the world’s greatest art work. It is indeed a remarkable painting. What we found fascinating was the way Velázquez, looking directly out at us from his easel to the left, drew us into the picture.

When I first saw The Maids of Honour many years ago, it was in a room by itself with a large mirror on the wall opposite it. Looking into the mirror, I got the distinct impression that I was in the picture. I’m sorry that the painting’s present location doesn’t allow for that bit of magic.

The Surrender of Breda (a town in Holland taken by the Spaniards in 1625, after a long siege) drew our eyes to the two central figures, Justin of Nassau, the Dutch leader and Ambrosio Spínola, the Spanish commander. In this painting, we don’t see the dark side of war, but its potential for noble action.

Like the Maids of Honour, there are different interpretations of The Spinners. We liked the one that depicts the myth of Minerva (or Pallas Athena), goddess of the Arts, and Arachne, a young woman famous for her skill in weaving. So proud was Arachne of her skill that she even boasted of being better than Minerva. Minerva then disguised herself as an old woman to admonish Arachne but to no avail. Minerva won the ensuing contest between the two, and Arachne was transformed into a spider as punishment. What is interesting is how Velazquez has “demythified” the classical world of gods, and brought them down to earth.

In The Drinkers/Bacchus, we enjoyed Velázquez’s irreverent treatment of classical mythology.

A mischievous looking Bacchus looks away while placing a garland on a kneeling drinker who is accompanied by fellow drinkers. These are wonderful looking characters who might have stepped out of a picaresque novel, so much in vogue in Spain at this time.

Goya is the art giant of the 18th century. Like Velázquez, Goya became a court painter but he embraced all levels of Spanish society, from the underworld of prostitutes to the salons of the nobility.

Born in the Age of Reason, Goya painted with the passion of a romantic. Saints and sinners, the Inquisition, the church, bullfighting, war, Spanish customs, human foibles and superstitions, ignorance, pretentiousness, all came under his critical eye. Goya tears away the façade of society and reveals the darker side of human nature.

Goya does not flatter; if anything he “demythifies”. Royalty and nobility are painted warts and all.

Look at the painting of The Family of Charles IV. The French novelist Theophile Gautier famously described the king and queen as looking like “the corner baker and his wife after they have won the lottery” despite wearing the robes of royalty. The king -who is not even the focal point of the work- wears a vacant expression, and the queen -with her hard set mouth, double chin, prominent neck and large arms- is anything but regal.

If El Greco painted with mystical passion and Velázquez with dignified tranquility, Goya painted with visceral emotion. I usually end up drained if I spend too much time with Goya. And for pre-teens like Andrew and Alex, a little Goya goes a long way.

John: The Prado: As one of the greatest art museums in Europe, it is a must-see although don’t try to see too much at a time. It can seem overwhelming when you realises just how much significant art from so many periods are housed here. We spent around 3 hours today and I would say that that was pretty much perfect for one day. We wanted to expose our children to some of the master,s and I also wanted to be sure to see a few of my old favourites again. For me, this is a must see if you are to be in Madrid.

************

We left the Prado and headed south for the Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, about 10-15 minutes away. A wintry chill hung in the air, and streets in this area were closed to traffic owing to the Madrid marathon. We passed the Botanical Gardens, crossed at the Plaza del Emperador Carlos/ Charles V and were soon at the Calle de Santa Isabel, where the Reina Sofía is located. If you take the metro/ subway, you get off at Atocha Station (also the railway hub for the south).

Like the Prado, the Reina Sofía occupies an 18th-century building, originally known as the Hospital General de San Carlos. It underwent major renovation and opened in the 1980s with emphasis on contemporary Spanish art. In 1992, two ultramodern glass elevators were added to its exterior.

There was a long queue when we got to the museum, and waiting in the cold wasn’t a pleasant prospect. Fortunately, we learned that we were in the queue for a Dalí exhibition, so we quickly joined a smaller line-up for general entry and soon were inside. After a rather chaotic experience finding a locker, we were able to move on.

Although the Reina Sofía has works by Dalí, Miró, Gris, Tapiés and others we were there exclusively to see Picasso’s Guernica, one of the most famous art pieces of the 20th century, and perhaps the most horrifying denunciation of the atrocities of war ever painted. Commissioned by the Spanish government to paint something for the Spanish Pavilion at the Paris World Exhibition of 1937, Picasso spent months seeking inspiration around the idea of “painter and studio.” However, the decision was made for him following the near annihilation on April 26, 1937, of the sleepy Basque market town of Guernica by German planes helping General Francisco Franco overthrow the legitimately elected Spanish government. Picasso was outraged and, after working feverishly on numerous sketches produced a monumental 11½ by 25½ foot black and white canvass by the end of June.

Following Picasso’s wish that Guernica only go to Spain after the return of democracy, the painting was exhibited in the Museum of Modern Art in New York until 1981. It then passed to the Prado before finally being transferred to the Reina Sofía in 1992.

After seeing the smallish sketches and studies that led to the final product, we entered room 206 and were taken aback at the sheer size of and violence depicted in the painting.

We had just seen dignity portrayed in Velázquez’s Surrender of Breda, and cold blooded killing in Goya’s Third of May 1808, but nothing could prepare us for the totally dehumanised destruction and suffering depicted in Guernica. This was actually not so much about the town, Guernica, but about Picasso’s view of war. We have no clue that this refers to a specific event, at a specific time and in a specific place other than the title Guernica. By removing these common features, Picasso made his painting universal and timeless: this is what all wars do, create horror, destruction and suffering.

********

By the time we left the Reina Sofía, it was late afternoon and traffic had returned to normal. It was still chilly as we walked back up the Paseo del Prado. The paintings had clearly had an impact on Andrew and Alex, and they talked enthusiastically and intelligently about the different kinds of works they had seen.

On the way up the Paseo del Prado, we noticed what seemed to be a garden hanging on the wall of one of the buildings! This indeed is what it turned out to be, clinging to an exhibit hall funded by the Caixa (Credit Union) Forum, and installed in 2008.

At the Hotel Palace, we turned left and proceeded past the Greek-style Cortes (Spanish Parliament) building along the Carrera San Jerónimo to the Puerta del Sol. Here Margaret and I separated from John, Leslie, Andrew and Alex. They headed for the Palacio Real (Royal Palace) which is not the home of King Juan Carlos and Queen Sofía, although it is still used on state occasions.

I once did some research in the palace library, and took the opportunity to see the treasures of one of the most lavish royal palaces of Europe.

Margaret and I went to look for somewhere for a late lunch and ended up in the Plaza Mayor. We had a very enjoyable meal at El Portal, right at the eastern entrance to the square. Tea for each of us, two bowls of hearty Galician style soup (caldo) brimming with potatoes, cabbage and chunks of chorizo (perfect for the weather) followed by a generous plate of crisply fried, lightly battered anchovies (nothing like the tinned variety!). For 24 euros, it was a good find, especially considering that touristy venues like the Plaza Mayor are not the cheapest or necessarily the best places to eat.

It was raining by the time we got back to Hotel Los Condes and John, Leslie, Andrew and Alex arrived soon after. After some discussion, Margaret and Leslie decided –since we were leaving the next day- to do some laundry. Now, self-service launderettes (or laundromats) are very difficult to find in Spain, and using hotel facilities (which usually turn out to be contracted private laundries) is expensive. So, we were delighted to discover, just a few yards away from the hotel, a laudromat, with clear instructions in English as well as Spanish.

After helping carry the clothes to the laundromat, John, Andrew and I left to have a bite to eat. Although not particularly hungry, I was persuaded by Andrew’s enthusiasm because by now he was something of a connoisseur of fried, battered calamares (squid), and he, mum, dad and sister had found a place -bar/cafe El Jamón on the Gran Vía, about 5 minutes from our hotel- that made great bocadillos (baguette-style sandwich) of calamares. He was right. A glass of beer and a couple of delicious bocadillos later, we walked back to the laundry, just in time to carry the now clean clothes back to the hotel!

El Greco’s Adoration of the Shepherds: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AdoracionPastoresElGreco2.jpg

El Greco’s image of Saints Andrew and Francis. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:El_Greco_038.jpg

Velazquez’s Las Meninas: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Las_Meninas_(1656),_by_Velazquez.jpg

Velazquez’s Surrender of Breda: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Velazquez-The_Surrenderof_Breda.jpg

Velazquez’s The Spinners: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Vel%C3%A1zquez_-_La_F%C3%A1bula_de_Aracne_o_Las_Hilanderas_(Museo_del_Prado,_1657-58).jpg

Velazquez’s The Drinkers: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Vel%C3%A1zquez_-_El_Triunfo_de_Baco_o_Los_Borrachos_(Museo_del_Prado,_1628-29).jpg

Goya’s The Kite: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:La_cometa.jpg

Goya’s Third of May 1898:http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:El_Tres_de_Mayo,_by_Francisco_de_Goya,_from_Prado_thin_black_margin.jpg

Goya’s Family of Charles IV: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Francisco_de_Goya_y_Lucientes_054.jpg

Picasso’s Guernica: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:PicassoGuernica.jpg