Golden Age Religious Painting and Italian Influence in the 16th Century.

Introduction.

The vast majority of paintings produced in Spain’s Golden Age (in general terms the late 15th, 16th and 17th centuries) were religious, and most were sponsored by the wealthiest institution in the country: The Catholic Church with its affiliated monasteries, convents etc.

Although there were plenty of Spanish artists engaged in painting works for the church etc. during the Golden Age they were frequently overlooked in favour of foreign painters, especially from Italy and Flanders. Italy figuring prominently is not unexpected, given its established leadership in so many cultural branches of the Renaissance **.

**It should be kept in mind that Italy as a united political entity did not exist during the Renaissance. What is now Italy was during the 15th century made up of numerous republics or city states and the papacy, more often than not at odds with each other as they struggled to impose themselves on neighbouring regions. In the early 16th century, the Italian peninsula became a battle ground between Spain and France, with Spain –under Charles V—emerging victorious. Spanish military domination prevailed throughout the peninsula, although many cities retained their identity either as duchies or as republics. The papacy remained in charge of Rome.

The pursuit of humanistic scholarship in Italy opened up new avenues of thought further stimulated by the competitive spirit between the main Italian city states of the time (Florence, Venice, Naples, Rome, Milan, Ferrara).

Scholars, poets, artists, sculptors etc. from other European countries arrived in these intellectual centres in a steady stream, eager to acquaint themselves with new ideas inspired by classical culture and with the latest techniques (e. g. linear perspective and sfumato i. e. the blending of tones and outlines).

There were other visitors too, merchants, bankers, pilgrims, soldiers (Italy was the scene of regular conflicts and wars), who, whether consciously or not, were exposed to new experiences that they carried back to their own countries.

Nevertheless, traffic was not all one way: Italian artists travelled to European countries invited by wealthy patrons, and visitors to Italy sent back paintings, reproductions and engravings to their home countries which were then often copied by artists there.

Most of the giants of Renaissance art were Italians belonging to the 15th and 16th centuries who enjoyed widespread fame and prestige (e. g. Piero della Francesca 1406-92, Botticelli 1444-1510, Raphael 1483-1520, Leonardo da Vinci 1452-1519, Michelangelo 1475-1564, Titian 1488?-1576, Correggio 1489-1534, Tintoretto 1518-94).

Italian Renaissance painting did not have much impact in Spain until the late 15th century, by which time Italian painters had become skilled at the use of oils first mastered by Flemish artists such as Jan van Eyck (ca 1390-1441). As a result, Italian influence was initially less marked than that of Flemish art, especially in Castile.

Where it was first felt was in Valencia where Cardinal Rodrigo Borja (the future Pope Alexander VI, born in Xátiva, Valencia) introduced three Italian artists to city in 1472. One of these painters was Paolo da San Leocadio (1447-ca 1520). Born in the northern town of Reggio Emilia (north west of Bologna), Paolo brought with him a distinctive style practiced in Italy, especially by Leonardo da Vinci, and quite different from Flemish painting.

What follows is in no way an exhaustive analysis of the influence of Italian religious art on Spanish religious painting, nor is it intended to trace the evolution of individual artists. Rather, the aim is to identify, in a limited number of works, important characteristics of Italian religious painting which appeared in Spanish art from the end of the 15th century and into the 16th.

We can begin by summarising those characteristics as follows: a tendency towards serene, feminine idealisation (a demure Virgin Mary or female saint with downcast eyes and long golden tresses), classical settings (e. g. buildings) and/or softly-coloured landscapes, sfumato (blurred contours) and chiaroscuro (contrast in which light falls on the main character(s) against a dark background), angelic cherubs and putti (from putto: a male child, frequently naked and chubby). Often faint halos surround the heads of holy figures. However, male figures (including saints, apostles) were much more realistically portrayed, conveying real emotions in keeping with the emphasis on individual worth and dignity advocated by humanism.

Let’s start with a painting by Paolo da San Leocadio: Virgin and Child with St John (ca 1510), now in the Museu de Belles Arts de València).

It’s a work that captures the Italian Renaissance spirit very well. The Virgin’s idealised look -golden hair, pale face and blue eyes- and her gentle gaze are very much in tune with descriptions of ideal feminine beauty in Renaissance poetry.

The curly, golden-haired baby Jesus is a well-fed, chubby putto and the infant John the Baptist is only a little less plump. Both wear faint halos.

The landscape, although fairly hilly is, unlike that of Flemish paintings, marked by soft greens and blurred contours. The niche at the top right with a small nude statue on a pedestal hints at classical sculpture. Finally, the triangular composition of the three figures was used widely by Italian painters.

Two Spanish artists very much influenced by Italian painting were Fernando Yáñez de la Almedina (ca 1475-1540) and Fernando Llanos (?-?), active in Spain 1506-16). Both were from Castile-La Mancha, both went to Florence where they worked with Leonardo da Vinci. Returning to Spain around 1506, they collaborated in painting twelve panels that served as shutters for the altarpiece of the cathedral of Valencia. After that, they seem to have gone their separate ways.

Around 1505 (perhaps while still in Italy), Yáñez produced a Madonna and Child with Infant St John which has a striking resemblance to San Leocadio’s version above. Clearly, since it precedes San Leocadio’s version, Yáñez did not imitate the Italian painter.

The point is that they both belong to the same artistic thinking, and in fact may well have had Leonardo’s Madonna of the Yarnwinder (ca 1501) in mind.

The idealised, delicately featured Mary, with traces of golden hair, the softly-contoured landscape and the triangular composition of the three figures belong to the same world as San Leocadia’s version. So too, baby Jesus and the infant John the Baptist, both are curly-haired, twin-like putti whose embrace was probably inspired by Leonardo’s Holy Infants Embracing, 1490 and repeated by numerous painters

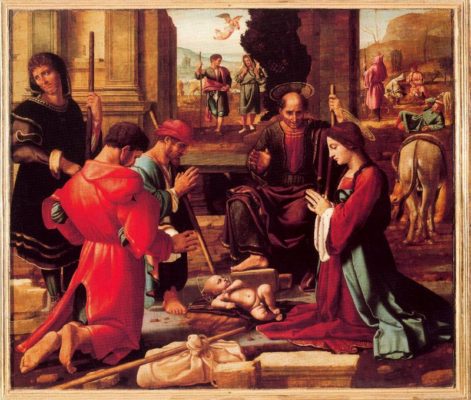

Yáñez’s collaboration with Fernando Llanos on the shutters of the High Altar has led to some disagreement about the authorship of each panel. We’ve taken two panels, the first -the Adoration of the Shepherds 1507-10— is acknowledged to be by Yáñez; the second –the Death of the Virgin 1507-10- is more problematical but according to the art historian, Jonathan Brown (13), it shows the hand of Fernando Llanos. Both paintings are on the outside of the shutters covering the wooden stature of the Virgin Mary to whom the altar is dedicated.

Both paintings reflect the Italian orientation of the artists, combining religious iconography (heavenly angels floating on puffy clouds, a demure Virgin with downcast eyes, saintly individuals with halos, a chubby child Jesus) and secular realism (individual male figures with natural poses, and -in the Adoration- daily activities).

Both scenes are set, anachronistically, against monumental classical architecture, and a softly contoured landscape background in the Adoration. The composition with its large number of figures follows the practice of Italian painters: some individuals converse in groups, others are absorbed in their own thoughts or gaze — as if distracted- beyond the frame.

Yáñez’s painting Rest on the Flight to Egypt (1507-10) is in the interior of the shutters covering the wooden stature of the Virgin Mary. It is divided into two contrasting halves.

To the left, the pose of the Virgin and Jesus is similar to that found in his Madonna and Child with Infant St John, but added now are playful cherubs (angels) who have attracted the chubby, curly-haired Jesus’s attention. Scarcely visible halos cover the heads of the three holy fugitives. The left side of the painting has a other-worldly quality, from the angels, the Virgin’s calm repose and the vaguely outlined building(s) on a hilltop in the background.

To the right, the busy Joseph, reaching up to grasp some palm fronds, dominates the scene. Although his stance may seem somewhat contrived, there are realistic touches to his face, the tense neck muscles and his powerful arms and hands. These realistic features, together with the cow and donkey behind him adding a common detail, suggest Flemish influence. In the background, above the cow, the flight to Egypt is seen “in action” with Mary now seated on a donkey, Jesus on her lap and Joseph walking in the lead.

Although Valencia was the main entry point of Italian artistic practice in Spain, Toledo and Seville soon became centres of activity. Pedro Machuca (1490-1550), better known as the architect who designed Charles V’s Renaissance palace in Granada’s Alhambra complex, was from Toledo. He worked in Italy from about 1510 to 1520 and possibly trained under Michelangelo and Raphael.

An early work –Virgin of the Souls in Purgatory (1517) painted by him while still in Italy— depicts an extravaganza of haloed putti on puffy clouds surrounding the golden-haired Virgin as she and baby Jesus squeeze milk from her exposed breasts to the souls in purgatory at the foot of the painting.

Although images of a nursing Mary were not uncommon, Machuca’s choice of her feeding (and giving hope to) those in purgatory is original and daring. It’s not a common topic in Spanish art, and suggests a certain boldness on the part of Machuca.

Another painting, the Deposition (ca. 1520-25) is a very personal even eccentric interpretation of Christ’s descent from the Cross.

Recognisably Italian are the sculpted figure of Christ (reminiscent of Michelangelo), the golden-haired Mary Magdalene waiting to receive him, the weeping group of women at the bottom left and the Raphael-type individual supporting Christ’s shoulders. Chiaroscuro highlights the luminosity of Christ’s body and Mary Magdalene holding Christ’s shroud against a dark background and shadowy figures. The rest is really a personal and imaginative jumble of bizarre characters, above all the weirdly dressed group at the bottom right who seem to be totally oblivious to what is going on.

Another artist, Juan Correa de Vivar (ca. 1510-66) was from a village near Toledo. His Annunciation (ca. 1550), now in the Prado Museum contains many elements of Italian religious iconography: the modest, golden-haired Virgin, her expressive hands, the heavenly cherubs, the bearded God the Father reaching out from the cloud (à la Raphael), and the dove fluttering above Mary.

The elegant, flowing and slightly elongated figure of the Archangel Gabriel as he arrives with news to Mary (that she is to give birth to Jesus) is also drawn from the artistic vocabulary of Italian painters. The setting is contemporary Italian, from the classical pillar in the background to the tiled floor and the Renaissance table supporting an open book. The anachronistic use of contemporary settings might well be seen as a way of conveying the point that the Christian message is timeless, and as meaningful in the 16th century as at the time of Christ’s life and death.

Luis de Morales (ca 1509-86) spent most of his life in Badajoz (Extremadura), where he was probably born. A prolific artist, Morales was known from early on as “El Divino” because of the emotional intensity of his paintings. Although he executed commissions in large and small churches (e. g. the cathedral of Badajoz or the parish church of Arroyo de la Luz (known as Arroyo del Puerco until 1937), Morales worked primarily for individual clients.

He specialised in intimate biblical scenes, from Virgin and Child to the Passion of Christ (Christ’s sufferings from the Last Supper to His death and descent from the Cross).

One of the best known of his many versions of holy Mother and Child is the Nursing Virgin (c. 1565) in the Prado Museum. By the time Morales was painting, Italian style paintings of Virgin and Child had become a cliché.

But Morales was able to inject unusual depth of tenderness and feeling into this painting. Thanks to his mastery of the sfumato technique, he has softened the framework while at the same time highlighting Mother and Child.

By eliminated external distractions, Morales leaves worshippers to meditate exclusively on the intimate relationship between mother and child both on a human and divine level.

On the human level, it is a tender moment with a child gazing at his mother while with one hand he searches for her breast and with the other clutches her veil; for her part, his mother’s prominent hands cradle him with protective gentleness.

On the divine level, it evokes compassion since the tragedy awaiting the Child would be known to everyone and the melancholy on Mary’s face understandable.

That tragedy is captured by Morales in his Pietà (1560-70) painted for a Jesuit church in Córdoba but now in the Real Academia de Bellas Artes, Madrid. The softness which characterises all aspects of the Nursing Virgin is replaced by a much more dramatic “hard” vision of Mother and Child in the Pietà intended to evoke compassion in worshippers.

Employing chiaroscuro effectively, Morales throws light on Christ’s body –which takes centre place- contrasting it dramatically with the dark background and the deep blue of his Mother’s cloak. It is a tender and intimate moment but starkly rendered. The Virgin’s strong hands now support and cradle her son’s unresponsive body. Blood runs down prominently over his ribs from the gash on his right side. His head is thrown back, his eyes are lifeless, his arms hang helplessly down to dramatically positioned hands.

The realism and eye for minute detail with which Christ is depicted suggests Flemish influence. Indeed, through clients of his in Seville, Morales may well have met the Flemish painters Pieter Kempeneer and Hernando Sturmio who were working on paintings for the cathedral in Seville at that time.

Morales’s prolific production of pieces focussing on the life of Christ or portrayal of saints reflects an increased religiosity in Spain in the second half of the 16th century. Much of it was inspired by the Catholic Church’s call to counteract the Protestant Reformation promoted by Martin Luther and others.

Reforms were proposed and formulated by a Council of Catholic theologians in a series of meetings held in the town of Trent in northern Italy between 1545 and 1563. Out of the deliberations at the Council of Trent came directives that defined Catholicism’s Counter-Reformation. In art, painters were urged to encourage piety by drawing on biblical topics that would elicit compassion, particularly the Immaculate Conception, the Madonna and Child, Christ’s Passion and the Pietà. Saints and martyrs were also worthy subjects.

Artists were further encouraged to focus on the subject matter and eliminate unnecessary or irrelevant ornamentation. They were especially recommended to render their paintings as direct, compelling and as relevant as possible to ordinary people.

The distinctive features of Italian painting were so embedded in Spanish art by the end of the 16th century that they became commonplace. But this is the time when Spanish artists began to assert their independence giving rise to the Golden Age of Spanish Painting.

Like Cervantes who absorbed earlier novelistic fashions (e. g. romances of chivalry, pastoral and picaresque novels) to produce his highly original Don Quixote (1605, 1615), Spanish artists combined earlier artistic approaches (i. e. Italian and Flemish) with their own inspiration to produce highly original pieces widely recognised as a rich contribution to the history of Western art.

Sources.

Brown, Jonathan Painting in Spain 1500-1700 New Haven and London 1998

Glendinning, O. N. V “The Visual Arts in Spain,” in Russell, P. E. ed. Spain. A Companion to Spanish Studies, pp. 473-542 New York 1987

Museo Nacional del Prado The Prado Masterpieces New York 2016

Royal Academy of Arts The Golden Age of Spanish Painting Uxbridge, England 1976

San Leocadio, Paolo da: Virgin and Child with St. John: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3294134

Yañez, Fernando: Madonna and Child with Infant St John: http://pintura.aut.org/SearchProducto?Produnum=54654, Dominio público, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10558141

Yañez, Fernando: Adoration of the Shepherds: http://www.catedraldevalencia.es/en/recorrido-por-la-catedral42.php

Llanos, Fernando: Death of the Virgin: http://www.catedraldevalencia.es/en/recorrido-por-la-catedral42.php

Yañez, Fernando: Rest on the Flight to Egypt: http://www.catedraldevalencia.es/en/recorrido-por-la-catedral42.php

Machuca, Pedro: Virgin of the Souls in Purgatory: https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/artist/machuca-pedro/590bd4dc-8c3e-43e9-9097-ef8da2e36d21

Machuca, Pedro: Deposition: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pedro_Machuca_-_Deposition_-_WGA13800.jpg

Correa de Vivar, Juan: Annunciation: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juan_Correa_de_Vivar

Morales, Luis de: Nursing Virgin: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luis_de_Morales

Morales, Luis de: Pietà: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Luis_de_Morales_-_Piet%C3%A0.jpg

For Italian paintings in the Prado Museum, see https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/italian-painting