Themes in Painting in the Spanish Golden Age.

Religious Paintings.

The vast majority of paintings produced throughout the 16th and 17th centuries in Spain were religious, in response to demands both at home and in Spain’s distant colonies of Mexico and Peru. Flemish and Italian artists were initially favoured by Spanish patrons over native painters owing to their mastery of new painting techniques and the prestige they enjoyed. (See Overview for more details)

The Catholic Church had always recognised the impact of paintings (and sculpture) to reinforce religious messages. This was especially relevant at a time when Catholicism was being challenged by the birth of Protestantism with its emphasis on simplicity and frequent rejection of painting (and sculpture) as idolatrous.

The Catholic Church’s response to the Protestant Reformation was formulated in a series of meetings held in the town of Trent in northern Italy between 1545 and 1563. Out of the deliberations at the Council of Trent came directives that defined Catholicism’s Counter-Reformation. In art, painters were urged to encourage piety by drawing on biblical topics or saintly figures that would elicit compassion, particularly the Immaculate Conception, the Madonna and Child, Christ’s Passion and the Pietà (Mary cradling Christ’s lifeless body after His descent from the Cross).

This might be expressed in three general ways:

1. Believers could be moved by scenes of angelic hosts or other heavenly figures (e. g. doves) hovering in swirling clouds above the Virgin or saints etc. very much in the Italian tradition. These kinds of paintings are noted for their sense of movement intended to evoke a sense of awe and wonder at the miracle(s) or heavenly activities unfolding. For example, The Annunciation by the Italian born Vicente Carducho (c. 1576-1638), who moved to Spain with his older brother when he was only 9 and who became royal painter in Philip III’s court in 1609.

A second example is The Mystic Marriage of St. Agnes (1628) from Francisco Pacheco, artist and theoretician from Seville, probably better known now as father-in-law to Diego Velázquez, Spain’s greatest Golden Age painter.

2. But artists were also encouraged to focus on the subject matter and eliminate unnecessary or irrelevant ornamentation and render their paintings as direct, compelling and as relevant as possible to ordinary people. For example, Luis Morales’s Pietà focuses exclusively on Mary, and Christ’s body, bathed in light against a black background. It is a key dramatic yet intimately tender moment: the sorrowful mother whose prominent hands support her dead son, Jesus, and Jesus’s lifeless eyes, limp arms, curled hand and twisted body with its bloody gash. All irrelevant material has been removed.

3. A complementary approach to the two approaches to religious devotion above was to paint biblical or religious figures realistically, in ordinary contemporary clothes, the contemplation of which would bring the biblical world or the world of saints closer to the viewer. The tone was set by the irreverent Italian Michelangelo Caravaggio (1571-1610) whose religious figures often looked like peasants albeit dramatised by the artist’s use of near theatrical lighting.

A painting, The Death of St. Francis (1593), by Bartolomé Carducho, older brother of Vicente, is a good example of contemporaneity. [Bartolomé c.1560-1608 moved to Spain with Vicente, in 1585, worked in the Escorial and became royal painter in the court of Philip II in 1598.] Churchgoers, seeing the Franciscan monks, would immediately recognize them from their rough habits/ robes and empathise with their grief. The dying saint’s habit is threadbare and his bare feet are dirty. On the raised floor beside him are his discarded sandals next to a chamber pot. Nothing could be more down to earth.

Portraiture.

After religious topics, portraiture was the most widely practiced form of art in the Golden Age. At first, modest portraits of devout donors appeared discreetly to one side or in side panels of religious triptychs (a painting consisting of a central panel and two side panels), attesting to their high social status and their piety.

From there, it was a short step to individual portraits, primarily of royalty, nobility, church dignitaries and other wealthy individuals (e. g. merchants). In each case, they denoted power, wealth, status.

By the beginning of the 17th century, however, pictures of ordinary, even low-born individuals began to appear, reflecting a move towards an increased interest in a realistic rendering of every day life evidenced in, e. g. Velázquez’s Old Woman Frying Eggs (1618). (There is a similar interest in literature, in for example, the low born pícaro —e. g. Mateo Alemán’s Guzmán de Alfarache, Cervantes’s short story Rinconete y Cortadillo or Quevedo’s El Buscón— or popular romances (ballads) depicting life in the criminal underworld.)

Overlapping and complementing this interest in the ordinary was the attention paid to STILL-LIFE and GENRE painting, e.g bodegones (low eating places). E.g. Velázquez’s Old Woman Frying Eggs 1618, and Zurbarán’s Still Life with Lemons and Oranges and Rose, 1633), which presented artists with new themes and technical challenges. Sometimes it is difficult to distinguish between still-life and bodegón paintings: e. g. The Old Woman…. contains kitchen utensils and eggs that are, in effect, examples of still-life; Zurbarán’s Still Life… speaks for itself.

What is not much found in Spanish painters are mythological, nude and landscape canvases. Mythology and nudity went hand in hand and many wealthy Spaniards (notably Philip II) had large collections, but almost exclusively by Italian artists. Opposition by the Catholic Church was undoubtedly a formidable deterrent to Spanish painters, as was the competition presented by Italian painters.

Nevertheless, Velázquez painted one of the most famous and sensual nudes in art: Venus and Cupid (1648) aka Venus at her Mirror or the Rokeby Venus (so named after the country house in Yorkshire, England where it hung from 1813 to 1906 when it passed to the National Gallery, London, where it still hangs).

Landscape had long been used as a background to the main theme of a painting: e. g. in religious scenes, portraits (e. g. Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa (ca. 1503-19), or incorporated into mythological narratives. As a topic in itself it was not taken seriously, and only at the end or the 15th century did it become the subject of a painting, and this almost exclusively in northern Europe, with works by Albrecht Altdorfer (1480-1538), Albrecht Durer (1471-1528) and others.

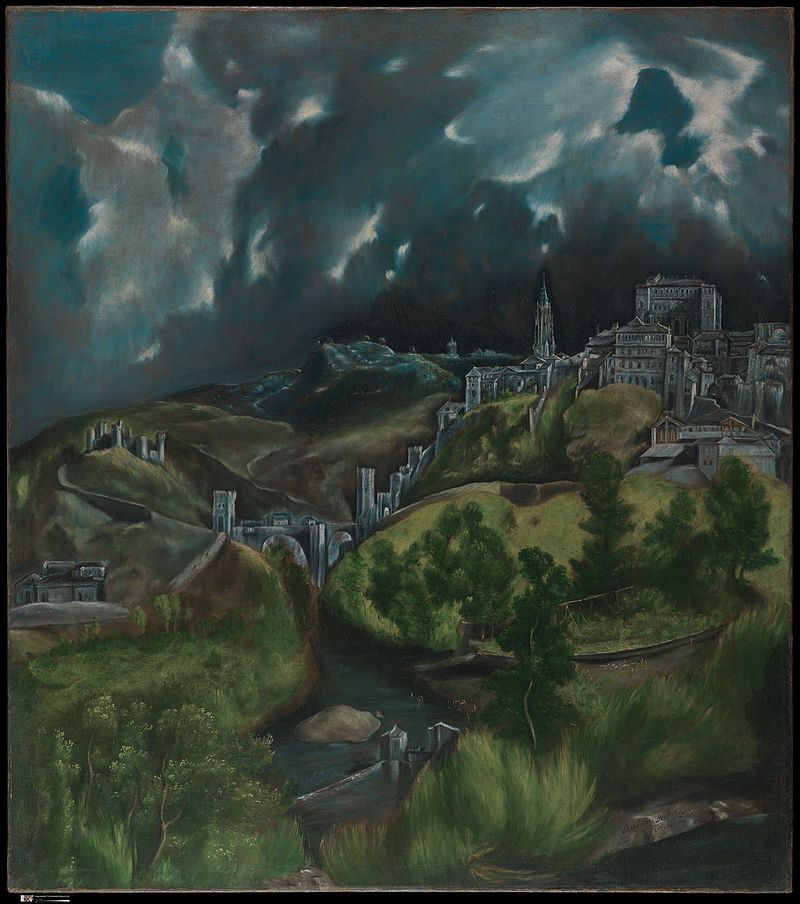

In 1600, however, a landscape painting appeared like no other before, or indeed perhaps since: El Greco’s View of Toledo (1595-1600), now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The first of two views of Toledo (the second is View and Plan of Toledo, 1608), it is clearly not a realistic reproduction (in fact, the cathedral and the Alcázar –top right of picture—have been reversed) but rather a landscape of the mind.

What El Greco did was transform Toledo from description to representation, offering us an unearthly rendition of the city –with a brooding, stormy sky hovering above it- as if it were about to be visited by divine presence, perhaps the omnipotent Old Testament God of Moses.

In the 17th century, some painters moved nature from the background of religious paintings to dominate the scene e. g. Francisco Collantes’s The Burning Bush c. 1634). Even so, it is often a dramatic, overpowering landscape where realism is subordinate to effect.

However, there are two notable exceptions both by Velázquez: views of the Villa Medici in Rome (in the Prado Museum).They are small impressionistic garden scenes of remarkable originality painted in 1630 during Velázquez’s first trip to Italy. Unsurprisingly, Velázquez was much admired by the Impressionists.

Sources.

Brown, Jonathan Painting in Spain 1500-1700 New Haven and London 1998

Glendinning, O. N. V “The Visual Arts in Spain,” in Russell, P. E. ed. Spain. A Companion to Spanish Studies, pp. 473-542 New York 1987

Royal Academy of Arts The Golden Age of Spanish Painting Uxbridge, England 1976

Luis de Morales: Pietà: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luis_de_Morales#/media/File:Luis_de_Morales_-_Piet%C3%A0.jpg

By Francisco Pacheco - [2], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6250249

By Vincenzo Carducci - [2], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=51760426

Carducho: Death of St. Francis: https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bartolomeo_Carducci

Titian. Portrait of Charles V: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Equestrian_Portrait_of_Charles_V

Velázquez. Old Woman Frying Eggs: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=19980800

Still Life by Francisco de Zurbarán: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15466896

Collantes, Francisco. The Burning Bush https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Francisco_Collantes

Velazquez: Venus and Cupid -The National Gallery, London. Retrieved on 25 June 2013., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=984326

Velázquez. Garden at the Villa Medici in Rome: By Diego Velázquez - Galería online, Museo del Prado., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=45401505