El Greco. Domenikos Theotocopoulos (ca. 1541-1614).

Few paintings are so easy to recognise as those of El Greco (ca. 1541-1614), and few have provoked such wide-ranging and contradictory reactions. Although celebrated when he died in 1614, he soon fell into obscurity.

A change of taste to realism, best illustrated by Diego de Velázquez’s bodegones and the popularity of Still Life, took over in the 17th century. During the 18th-century, El Greco’s painting was rejected as too radical and idiosyncratic for Enlightenment taste. It was only in the 19th century that El Greco was rediscovered.

By the early 20th century, he had won the admiration of numerous artists, from Impressionists (e. g. Manet, Cezanne) to Expressionists (e. g. Beckmann, Macke, Kokoschka). Picasso considered El Greco to be the quintessential Spanish artist, together with Velázquez and Goya. In 1902, the Prado Museum organised an exhibition of El Greco’s paintings, a kind of official recognition of his rehabilitated status. This was followed by several historical studies which cemented El Greco’s reputation, re-evaluating his art and examining his influence on contemporary painting.

An Unconventional Man.

What is it about El Greco and his painting that sets him apart? The word that comes to mind is “unconventional” both in life and art. Born Domenikos Theotocopoulos on the island of Crete, he received his early grounding in Byzantine iconography, then lived and trained for ten years (1567-77) in the Western Renaissance tradition in Venice and Rome before eventually leaving for Spain. He settled temporarily in Madrid before moving permanently to Toledo in 1577, when he was 36 years old.

At first an outsider, the self-confident and ambitious El Greco went on to make his name in the city that was the spiritual heart of Spain and its church the wealthiest in the land.

Toledo was also a centre of scholarly activity with powerful ecclesiastical and intellectual figures, many of whom, attracted by El Greco’s artistic originality, became friends and patrons. Among his admirers were the celebrated preacher Hortensio de Paravicino and the famous –and unconventional- poet Luis de Góngora.

Sure of his artistic talent, El Greco was unafraid to defend his interests, launching lawsuits, haggling boldly over fees for his paintings (even with Philip II’s assessors), or disregarding objections to details in his canvases. Indicative of his independent spirit was his life-long, common-law relationship with Doña Jerónima de las Cuevas, by whom he had a son, Jorge Manuel, in 1578. Jorge Manuel, an undistinguished painter, assisted his father in his workshop as well as becoming his business partner.

In a city “where God ruled” and religion seeped from its very walls, El Greco was a practical business man with a workshop, apprentices, woodcarvers, gilders, even an engraver –uncommon in Spain—whose work facilitated the distribution of paintings on a large scale. Nevertheless, although he lived a comfortable and perhaps lavish life-style, El Greco was frequently in debt over delayed payments and financial disputes with clients.

His sense of self-worth led him to fight for the right of painters to be seen as pursuing a noble art at a time when artists were considered mere craftsmen in Spain. Their status could not compare, for example, with that of artists in Italy, who enjoyed prestige and financial rewards.

This elevation of painting to a noble art as opposed to a craft was something El Greco pursued throughout his life. However, it eluded him, thanks to an ingrained attitude in Spain, and especially in Castile, towards manual work. Artists worked with their hands, sold their paintings, haggled over prices and paid taxes, all of which suggested manual work and was therefore looked down upon by nobility.

An Unconventional Artist.

There are several key adjectives that help us to understand what is unique in El Greco’s art: ethereal, dematerialised, disembodied, distorted, vertical, elongated, spiritual, translucent (with transparent qualities), mystical, poetic, supernatural, psychedelic, visionary, hectic, dynamic, swirling, insubstantial, unreal, unearthly, otherworldly, abstract, ecstatic, rapturous …

These adjectives are especially applicable to El Greco’s mature work, which for many, takes off after he executed his most famous work, The Burial of the Count of Orgaz 1586-88. Divided between two levels, between heaven and earth, the painting serves as a useful guide to the two worlds El Greco inhabited: the imaginative and the real. It is the former world that has made El Greco’s art unique, although he was also a brilliant realistic artist, as evidenced in the portraits he executed.

The Burial…, measuring 457 x 335 centimetres (15 x 11 feet) shows the entombment of the 14th-century Count of Orgaz, famous for his virtue and benefactor of several religious institutions. The painting is located in the church of Santo Tomé, Toledo, above the altar of the chapel where the count is buried.

According to legend, St. Stephen and St. Augustine (with beard) came down from heaven to place the count in his tomb. Behind them, a row of Toledo’s distinguished aristocracy has gathered to witness the burial. Two priests, a monk and a small boy (possibly El Greco’s son, Jorge Manuel) complete the group.

At this earthly level, El Greco has painted a realistic portrait gallery of Toledo’s nobility while the ecclesiastical vestments of Sts. Stephen and Augustine and the priest to the right are rendered in dazzling, meticulous detail.

So too the realistic details of the dead count’s glistening 16th-century armour and the remarkable translucent /transparent surplice of the priest with his back to us. The mood of the group is mournful, somber and contemplative. The entombment of the count is a transcendental moment and there is stillness and order in the gathering.

In contrast, the heavenly scene, is dominated by movement, by ethereal clouds swirling across the canvas, the elongated figures of the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist, and the prominent folds of the robes worn by the Virgin and other heavenly figures moving both vertically and horizontally.

There is little order with angels scattered among the clouds, and saints and martyrs -gathered to witness the arrival of the count’s soul—crowded into the upper right-hand corner. It’s a dynamic picture with all the movement channeled vertically through the Virgin and John the Baptist towards Christ the uppermost figure whose arms are open to receive the count’s soul. Even the shape of the frame moves our eyes upwards and inwards towards Christ.

The Burial of the Count of Orgaz reveals a confident and a self-assured painter both in his vision and execution. The composition is unique, the lines are bold and the colours vibrant. The striking yellow of the church vestments, the black of the mourning nobles, the different shimmering shades of white in the clouds, the transparent surplice, the shiny breastplate of the count etc. reflect the importance El Greco attached to colour, light and shading. They become basic tools in El Greco’s increasing interest in the portrayal of spirituality and otherworldliness.

It was once thought that El Greco’s style was the result of an eye defect that developed only after he arrived in Spain. That has long been debunked.

The roots of his style can be traced back to his training in Italy: the use and arrangement of colour to his Venetian years and the elongated figures with frequent muscular bodies and strained poses to the influence of Roman artists, especially Michelangelo. [This style of painting, with its love of exaggerated forms, is known as Mannerism.] Two paintings, executed shortly after arriving in Spain, point to the direction that El Greco was to take: The Holy Trinity (1577-79) and The Martyrdom of St. Maurice and the Theban Legion, completed in 1582.

The Holy Trinity, today in the Prado Museum, is Italian in spirit and composition, with echoes especially of the Mannerist style of Michelangelo. Christ’s body, arms and right hand are twisted awkwardly, and His legs crossed unnaturally under the weight. The angel to Christ’s right is elongated and has powerful, muscular legs.

The golden-haired angelic hosts and putti at Christ’s feet (putti, from putto: a male child, frequently naked and chubby) are very much in tune with Italian art. And the colours of the robes worn by God and the accompanying angels already show traces of the unique qualities associated with El Greco’s more mature works.

The Martyrdom of St. Maurice and the Theban Legion (1580-82) had a special significance in El Greco’s life. It was the painting he submitted to Philip II for an altar dedicated to St Maurice in the Escorial, the massive Royal Monastery built 60 kilometres (36 miles) north of Madrid between 1563 and 1584.

It was rejected by Philip probably because El Greco relegated the gruesome beheading of St. Maurice to the lower left-hand corner of the work in favour of a discussion between four soldiers in the foreground who appear to be oblivious to the Saint’s decapitation. Standing on rock above the scene of execution, they are powerfully built individuals with broad shoulders, elongated bodies and muscular legs. A prominent use of the hands suggests that the discussion is animated.

Elongated too are the bodies of those smaller figures contemplating the decapitated saint lying grotesquely upside down at the foot of the rock to the lower left.

The whole effect of verticality is complemented by the rectangular frame of the painting; everything is pushed upwards.

One striking feature is the bright colouration, dominated by different hues of blue, with unusual shades of red, green, yellow, brown. An angelic host floats to the upper left of the canvas mingling with transparent, swirling clouds which contain scarcely visible disembodied, ethereal forms.

What El Greco did in the 1590s and even more so in the early years of the 1600s was intensify and exaggerate those traits already evident in his early paintings in Spain pushing them to extremes. The result was to reveal the spiritual or supernatural world beyond the physical world, the intelligible beyond the world of the senses.

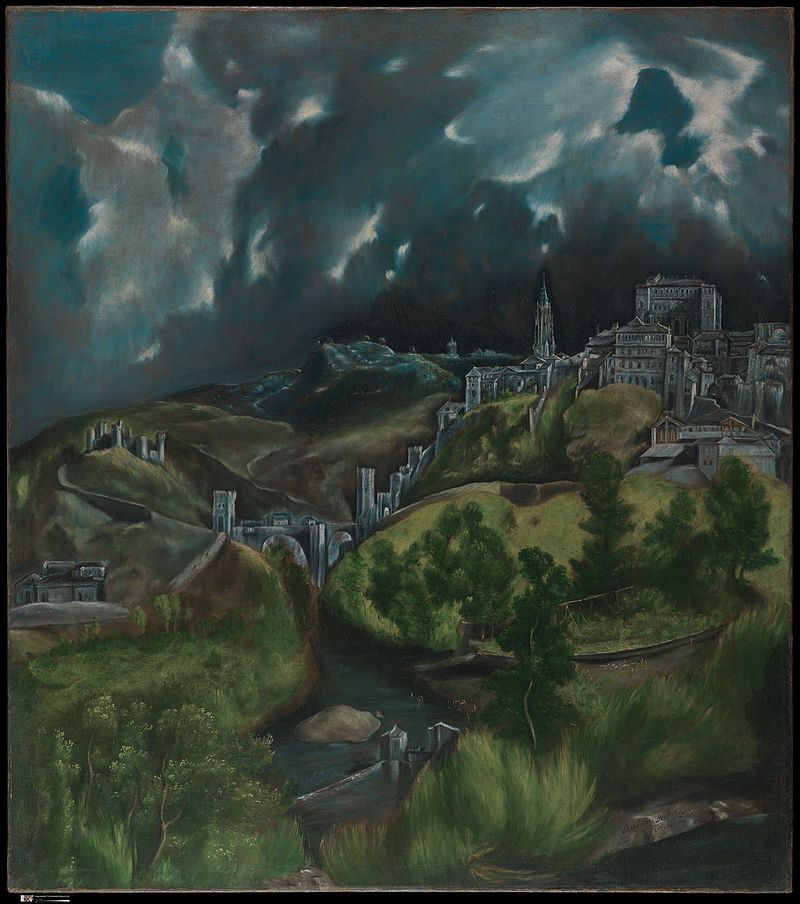

Sometime between 1595 and 1600 El Greco worked on a painting unlike anything he had done before: View of Toledo (1595-60), now in Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Usually referred to as a landscape painting, it is also unlike anything we usually think of as a landscape. The city stands, like Jerusalem (to which it has been compared) on a hill, its walls trailing down to the Tagus river and up the other side to the San Servando castle. But this is clearly not a realistic reproduction (e. g., the cathedral and the Alcázar –top right of picture—have been reversed.)

What El Greco has done is transform Toledo from description to representation. It’s an apocalyptic, supernatural vision with a dark, brooding sky of swirling clouds towering over the ashen coloured city and its walls with hints of bluish-green.

It is an unearthly rendition of Toledo -a meeting place between heaven and earth—as if it were about to be visited by divine presence, perhaps the omnipotent Old Testament God of Moses. The strange trees and the bushes in the foreground sway before the impending storm and there is little sign of human activity (a few tiny figures on the river bank).

The whole painting conveys movement, with curves dominating the composition travelling up and down and across the canvas. A serpentine road leads to large mound that merges into the sky beyond the city. The painting is a triumph of colour and light, but neither is easy to “grasp” as each blends with the other. Outlines are blurred and nothing is static in this dynamic vision.

The emphasis on colour, elongated figures and swirling movement became more pronounced as we pass into the 17th century.

The Immaculate Conception 1607-13 (347 x 174cm/ 11.4 x 5.7 ft), now in the Museo de Santa Cruz, Toledo, was originally an altarpiece located in the Oballe chapel in the church of San Vicente.

In the 17th century, paintings of the Immaculate Conception were especially popular. The theme, however, does not refer to the news that Mary received from the Archangel Gabriel that she would conceive a child whose name would be Jesus (that is known as the Annunciation).

Rather it refers to the conception of Mary without sin in the womb of her mother, St. Anne. What may appear confusing in paintings of the Immaculate Conception in the Renaissance is that neither Anne nor her husband, Joachim, are represented but rather Mary herself as an adult. Given its popularity, neither the Church nor contemporary viewers were concerned with theological accuracy.

El Greco’s version is the most dramatic, personal and easily recognisable of the many executed by his contemporaries. Seen from a kneeling position, this ecstatic vision –with all eyes facing the source of light, the Holy Spirit in the form of a dove, at the top- lifts us relentlessly upwards. There an angelic orchestra –a viol, lute, flute—greets the news joyously. Light, colour and form are distorted.

Elongated figures floating effortlessly in space, swirling robes, the dazzling effect of light off the shimmering red, blue, mustard yellow and white garments have a powerful, psychedelic effect intended to create awe and wonder. It’s a rapturous vision.

At the foot of the canvas a bouquet of roses and lilies, common symbols of the Virgin, are realistic touches while the outline of Toledo to the lower left is a small replica of the famous View of Toledo (discussed above), clothed in darkness.

The transition from darkness to light, from the earthly level (the flowers and Toledo) to the heavenly level represents a move from the real world to the spiritual. But by including Toledo, El Greco may also be paying homage to his adopted city. Joining the two worlds is a burst of light punctured by yellow lightening flashes emanating from or surrounding the cathedral tower. Toledo blessed by divine grace? It’s a tempting thought.

We’ll end with two examples of the many available that hardly need detailed commentary. The Adoration of the Shepherds (1612-14; 320 x 180 cm/ 10.5 x 6 ft) and St Peter (ca. 1610-14; (207 x 105 cm/ 7 x 3.5 ft).

The division between earth and heaven is nebulous in this nativity scene. It’s a completely dematerialised picture with extremely elongated humans and angels, the latter floating effortlessly in the clouds.

Suspended between them are amorphous baby forms. Light emanates upwards from baby Jesus illuminating the scene and revealing a tour de force of shimmering colours.

St. Peter, barefooted and wrapped in a heavily-folded, mustard yellow robe, stands appropriately on a rock (the name Peter comes from the Greek petros via Latin petrus, rock). The narrow frame accentuates the towering, elongated figure of the saint and the nebulous, shimmering background allows our concentration to be fixed solely on Peter.

The visionary, otherworldly nature of El Greco’s later works has been attributed to the increased religiosity of the second half of the 16th century in which mysticism featured prominently, e. g. Santa Teresa de Avila or San Juan de la Cruz (St. John of the Cross).

However, mysticism also faced strong opposition: by encouraging direct communion between believer and God, it threatened to undermine the role of the Church and its priests as intermediaries with God. In this sense, it evoked Protestantism which challenged Catholicism’s monopoly over the spiritual welfare of Christians.

The Catholic Church’s response to the Protestant threat was articulated the Council of Trent (a series of meeting of Catholic theologians in the Italian town of Trent between 1545 and 1563).

Out of the deliberations at the Council of Trent came reforms and directives that defined Catholicism’s Counter-Reformation. In art, painters were urged to encourage piety by drawing on biblical topics that would elicit compassion, particularly the Immaculate Conception, the Madonna and Child, Christ’s Passion and the Pietà (Mary cradling the dead Jesus below the Cross). Saints and martyrs were also worthy subjects.

Furthermore, artists were urged to eliminate unnecessary or irrelevant ornamentation and focus on clarity or simplicity of expression regarding the subject matter. They were especially recommended to render their paintings as direct, compelling and as relevant as possible to ordinary people (emphasis added).

The Church urged asceticism in place of mysticism and naturalism instead of exuberant imagination. El Greco’s paintings illustrate many of the themes advocated by the Council of Trent, but his interpretation deviates from the straightforward didactic narrative sought by the Church.

In dealing with the realm of the spirit, El Greco’s mature painting does find affinity with the mystical experience, but this spirituality may, in fact, be indebted as much to Neoplatonism as to Christian theology. Neoplatonism with its “subordination of the physical world to the world of the spirit” (Davies 4) or with the concept of the physical world as a shadow of a higher reality was a philosophy that found acceptance in Toledo.

In Neoplatonism, Christians found an “ethical and spiritual dimension [that] was akin to Christianity itself” (Walters 163). And, interestingly, an inventory of El Greco’s library showed that he had a Greek edition of a text by the Christian Neoplatonist, the Pseudo-Dionysius (late fifth or early sixth century AD. Davies 5).

Within this environment, El Greco probably aligned himself more with this philosophical stance than with the Christian mystic’s life of rejection of worldly goods. After all, he enjoyed a comfortable life style and was very much a business man, two matters that anchored him to the material world. A mystic, no, but a visionary, yes, when it came to transforming spiritual experience into art.

Sources.

Brown, Jonathan Painting in Spain 1500-1700 New Haven and London 1998

Davies, David El Greco Oxford 1976

Glendinning, O. N. V “The Visual Arts in Spain,” in Russell, P. E. ed. Spain. A Companion to Spanish Studies, pp. 473-542 New York 1987

Museo Nacional del Prado: The Prado Masterpieces Thames and Hudson, 2016

Royal Academy of Arts The Golden Age of Spanish Painting Uxbridge, England 1976

Walters, Gareth The Cambridge Introduction to Spanish Poetry Cambridge2002