Gothic Architecure: Background.

Gothic Architecture

Of all the buildings associated with the Middle Ages, few conjure up more admiration now than the Gothic cathedral. And yet it was not always so. In fact the description “Gothic”** was coined during the Renaissance as a derogatory term for bad taste when compared to elegant, classical architecture.

**“Gothic” still retains an element of disapproval:

Gothic novels, for example, are often characterised

by desolate settings, stormy skies and violent,

macabre incidents mixing horror and romance.

The Oxford and Webster dictionaries include

“barbarous,” “uncouth,” “rude,” in their

definitions of “Gothic.” Lately it has been vaguely

associated with the vogue for vampires.

Gothic novels, for example, are often characterised

by desolate settings, stormy skies and violent,

macabre incidents mixing horror and romance.

The Oxford and Webster dictionaries include

“barbarous,” “uncouth,” “rude,” in their

definitions of “Gothic.” Lately it has been vaguely

associated with the vogue for vampires.

Gothic architecture first appeared in northern France in the mid 12th century and evolved at a time of far reaching changes: population increase, new trade roots, economic revival, technological advances (from refined water-power techniques to improved commercial enterprises thanks to the introduction of Arabic numerals and the zero --via Spain-- and the introduction of paper --the first paper mill in Europe was opened in Spain in 1151), and a renaissance of intellectual activity best seen in the emergence of the universities in the 13th century: e.g. Bologna, Paris, Oxford, Cambridge, Salamanca. For some 400 years, the Gothic style dominated the architecture of Western Europe, inevitably leaving a profound legacy.

Like Romanesque, Gothic was a phenomenon admitting different kinds of buildings (palaces, castles, hospices, town and guild halls), but found its greatest expression in church related structures, in particular the great cathedrals that span Europe. The Church was after all the most prolific builder of the Middle Ages, and the one body that could move people to a common cause and gather money with relative ease to undertake large scale projects. Unlike Romanesque architecture, however, which radiated from rural monastic orders, and ranged in size from small rural churches to large cathedrals, Gothic churches were the fruit of urban interests and generally built on a large scale. Promoted by bishops, royalty and the city fathers of growing towns, their construction involved the entire urban population --merchants, townsmen, peasants,

"The faithful were for the

first time to be seen

pulling carts laden with stones, wood, wheat

and other supplies needed for the building of a

cathedral. … People everywhere humbled

themselves, did penance and forgave their

enemies. Men and women were seen carrying

heavy loads through bogs, singing and praising

the wonders of God….” “ Since the cathedral was

the symbol of God’s omnipotence, participation

in its construction became something akin to a

mystic experience. This explains the popular

character of Gothic style." Praeger 198.

pulling carts laden with stones, wood, wheat

and other supplies needed for the building of a

cathedral. … People everywhere humbled

themselves, did penance and forgave their

enemies. Men and women were seen carrying

heavy loads through bogs, singing and praising

the wonders of God….” “ Since the cathedral was

the symbol of God’s omnipotence, participation

in its construction became something akin to a

mystic experience. This explains the popular

character of Gothic style." Praeger 198.

*********

Gothic style has several characteristics that distinguish it from Romanesque, but in its general plan it shared many features with its predecessor: e.g. a long nave and two side aisles crossed by a transept, a choir and apse with ambulatory and radiating chapels, the use of towers, a major portal of the west front (usually three doors in the large churches). However, thanks to a new understanding of structural stresses, Gothic buildings rose to unprecedented height. Heavy Romanesque pillars or piers now gave way to compound slender piers, rounded arches over windows and portals changed to pointed arches, barrel vaults were replaced by ribbed ceilings, and walls were increasingly punctured by long stained-glass windows with decorative tracery that let in an enormous amount of diffused light. With the increased height of the walls and the prominent windows, external flying buttresses were added along the sides to prevent a collapse (even so there were disasters, e.g the vault of Beauvais, France).

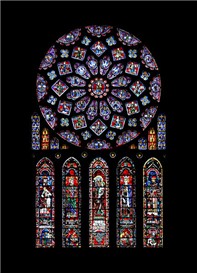

Following and adding to the Romanesque pattern, the west front of the large cathedrals was flanked by two impressive towers, now typically topped by spires or pinnacles. The entrance usually consisted of triple portals with pointed arches and several archivolts with sculptures depicting saints or bibilical figures or conveying a moral tale to the faithful as they entered the church. Above the portals a large circular rose or wheel window radiated outwards providing a focal point that at the same time pulled the whole front towards it. Rose windows also featured frequently above the east and west transept doorways.

What strikes visitors to the great Gothic churches is their luminosity, verticality and sense of weightlessness. If the Romanesque church was solidly rooted to the ground, the Gothic soared as if trying to break the bondage of stone to storm the heavens, and our eyes are drawn upwards pulled by the structure points of the arches, the slender pillars and the coloured shafts of light emanating from above. With the passage of time, the glass in some churches became overpowering: the dark blues and ruby reds almost reducing the light itself but at the same time giving it a luminosity that is almost palpable. If Romanesque comforts in its solidity, Gothic moves spiritually, even mystically some say, like a vision of paradise on earth, or a heavenly Jerusalem.

As was the case with Romanesque, Gothic style was not limited to architecture; it encompassed art, sculpture, and illuminated manuscripts. But there is one artistic feature of Gothic architecture that was especially outstanding: the use of stained glass. Although not unknown in Romanesque works, stained glass acquired particular significance in Gothic architecture, not surprising given the size of the windows. In many ways, stained glass was Gothic’s answer to Romanesque frescoes, and served a similar function: to teach as well as delight and move. Small illustrations of the lives of the saints and biblical scenes appeared in the chapel windows which were at eye level, but at the upper levels of the nave single, large figures were necessary for them to be visible. The striking effect of stained glass is evident on entering any of the large cathedrals.

*********

As with any form that lasted some 400 years and was prevalent throughout a wide area there was no complete uniformity of style. There was early Gothic, high Gothic, flamboyant Gothic, English, French, German, Italian, Spanish Gothic and so on. Clearly, from the international nature of both Romanesque and Gothic architecture, more cross border travelling took place than is generally credited for in the Middle Ages. Pilgrimages, commerce, royal marriages, alliances, wars (including the Crusades), ecclesiastical studies and appointments, the expansion of churches and monasteries, and the building opportunities offered to itinerant master masons, sculptors and craftsmen all stimulated travel.

Romanesque and Gothic entered Spain largely on the backs of travellers. Romanesque presence in Spain owed much to the cult of St. James (Santiago) and to the Benedictines monks of Cluny who facilitated the popular pilgrimage by building roads, bridges, monasteries, churches and shelters along the north of Spain to Santiago de Compostela. Gothic spread in similar fashion, often overlapping or combining with Romanesque. For example, the central town of Avila is just the place to see this transition from Romanesque to Gothic. It boasts some striking Romanesque churches, e.g. San Nicolás, Santiago and San Pedro. Its Romanesque walls (built between approximately 1088 and 1099) rank among the best in Europe. But two churches show the changing spirit: the granite Cathedral of San Salvador and the basilica church of San Vicente. The cathedral was started at the beginning of the 12th century, following Romanesque principles. However, around 1157, a major reconstruction took place the direction of a French (Burgundian) master builder named Fruchel so that it is now considered by many to be the first Gothic cathedral of Spain. Built like a fortress-church, with its apse incorporated into the famous walls, the cathedral continues in many ways the idea of Romanesque as the "church militant" that helped propel the Reconquista.

San Vicente lies outside the walls, and is primarily Romanesque but the nave is Gothic, the change being made when master builder Fruchel took over construction in the second half of the 12th century.

Historical note: The man responsible for the fortified walls of Avila was the French noble, Raymond of Burgundy, son-in-law of Alfonso VI (king of Castile-León (r. 1065-1109), and one of many French knights enlisted by Alfonso VI to consolidate his hold over the recently conquered Muslim taifa (mini state) of Toledo (Toledo was taken by Alfonso in 1085). At the same, several monks from Benedictine Abbey of Cluny arrived, invited by Alfonso VI to undertake reforms of the liturgy. It was they who introduced the Roman liturgy at the expense of the Visigothic liturgy (now known more commonly as the Mozarabic liturgy). French presence, then, was substantial and its impact far reaching.

Cistercian Architecture.

Given the close links between France and the Christian kingdoms of Spain in the 11th and 12th centuries (through e.g. marriage, the activities the Benedictines, French knights helping to repel the Almoravids and Almohads), it was virtually inevitable that French cultural impact would be felt. So it was that Romanesque art and architecture entered the peninsula, and the same applies to Gothic. Many scholars also point to the contributions of the rebellious offshoot of the Benedictines, the Cistercians, who objected to the decadent life style then enjoyed by the Cluniacs. The Cistercians erected some sixty strikingly simple, plain (to the point of austerity) monasteries along the north from Catalonia to Galicia. The most beautiful are probably the monasteries of Las Huelgas 1187 (Burgos), Santa María de Huerta 1179 (Soria), Santa María de Poblet ca 1170 and Santes Creus ca 1160 in Aiguamúrcia, Catalonia.

Sources:

Barral I Altet, Xavier ed Art and Architecture of Spain Boston 1998

Coldstream, Nicola Masons and Sculptors Toronto 1991

Dodds, Jerrilynn Architecture and Ideology in Early Medieval Spain Pennsylvania and London 1990

Heer, Friedrich The Medieval World New York 1962

Norman, Edward The House of God: Church Architecture, Style and History London 1990

The Praeger Picture Encyclopedia of Art, New York 1962

White, Robert A River in Spain: Discovering the Duero Valley in Old Castile London, New York 1998

Image of St Denis by Milkbreath: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basilica_of_St_Denis

Image of Leonby by Rastrojo : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Le%C3%B3n_Cathedral

Image of Chartres by Eusebius (Guillaume Piolle): http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chartres_Cathedral

Images of Avila by Roberto Abizanda : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%81vila,_Spain

Image of San Pedro, Avila by Håkan Svensson: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Avila_San_Pedro_View.jpg

Image of San Vicente by Outisnn: http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bas%C3%ADlica_de_San_Vicente_%28%C3%81vila%29

Image of Las Huelgas by Lourdes Cardenal: http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monasterio_de_Santa_Mar%C3%ADa_la_Real_de_Las_Huelgas

Image of Santes Creus by Josep Renalias: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Santes_Creus

Image of Santa María de Huerta by Ecelan: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Monasterio_de_Santa_Mar%C3%ADa_de_Huerta_-_Iglesia_-_Interior_desde_el_pie.jpg?uselang=es