Painting in Spain in the 18th Century: Francisco de Goya (1746-1828)

Even art lovers might have trouble in identifying any Spanish artists of the 18th century. The general lack of artistic talent is not limited to painting; in literature and sculpture, too, it is difficult to find any names that resonate. The one notable exception to all this is Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes (1746-1828).

The 18th century was, overall, a period of political embarrassment for

The 18th century also saw a foreign prince succeed to the Spanish throne. When the impotent Charles II, the last of the Spanish Hapsburg dynasty, died in 1700, he bequeathed the throne to the young French prince, Philip of Anjou. Under the new Bourbon dynasty, Spanish culture was heavily influenced by French and Italian taste, and many foreign painters were invited to the court at the expense of native artists.

An

It so happens that Goya was amongst those who competed for a place in the Academy. He was turned down, first in 1763 and again in 1766, without receiving a single vote from the judges. His temperament rebelled against the neoclassical formality imposed by the Academy.

Goya was finally elected a member of the Academy in 1780. By this time he had visited

From 1780 on, Goya moved up in the world. In 1783, he received a commission to paint the Count of Floridablanca, the Prime Minister of Spain. This was followed by portraits of members of the royal family, including one of King Charles III in 1786. In 1789, he was appointed court painter by the newly crowned Charles IV. Ten years later he was named first court painter.

In late 1792 early 1793, while on a trip to

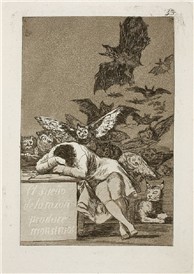

He continued painting portraits but at the same time developed an increasing interest in graphic work (etchings), the first series of which, (Los Caprichos: Caprices or Whims) were published in 1799.

These prints portray a much more personal vision of contemporary society with all its foibles, prejudices and injustices. These disquieting visions were to remain part of his artistic world for the rest of his life, intensifying if anything in their nightmarish quality as he grew older.

Goya does not flatter; if anything he “demythifies”. Royalty and nobility are painted as they are, warts and all. War is not heroic but savage and unfeeling. Goya tears away the façade of society and reveals the darker side of human nature. In the Age of Enlightenment (as the 18th century is frequently called), Goya plunges into our inner being, our unconscious, and exposes a frighteningly irrational and bestial world, sometimes with brutal frankness, sometimes with ironic humour. One of his best known prints from Los Caprichos bears the words “El sueño de la razón produce monstrous” (“The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters”). Beneath the print, a caption clarifies: “La fantasía abandonada de la razón, produce monstrous imposibles: unida con ella, es madre de las artes y origen de sus maravillas” (“Imagination abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters; united with her, she is the mother of the arts and the source of their wonders”).

Spain and Spaniards may be Goya’s subject matter, but their portrayal tells a lot about Goya himself, his views on society, its customs and institutions. He was in his way a psychologist, analyzing both himself and the human condition. He has something to say to all of us.

Image of La Cometa from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francisco_Goya#mediaviewer/File:La_cometa.jpg

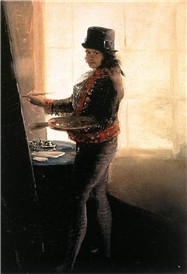

Goya self portrait from: http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Francisco_de_Goya_y_Lucientes_-_Self-Portrait_in_the_Workshop_-_WGA10008.jpg

Image of El sueño de la razón from Museo del Prado: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francisco_Goya