Lazarillo de Tormes: Summary

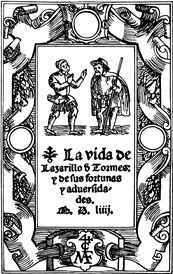

Lazarillo de Tormes pub 1554

Lazarillo de Tormes is a short but extraordinary work, published anonymously in 1554. It is structured as a letter in which the narrator, Lázaro –a wine taster and town crier in Toledo-- responds to a request made by an unnamed Vuestra Merced (Your Honour). Lázaro has to explain in detail to Vuestra Merced, seemingly his social superior, a certain “caso” (“matter”), the nature of which becomes clear only at the end of the novel/letter.

The book begins with a brief Prologue which is a brilliantly ambiguous: 1. It is written by an ostensibly uneducated town crier but alludes to several classical authors and is full of rhetorical devices; 2. Lázaro wants the letter to come to the attention of many readers and be praised, but it is addressed to one individual; 3. he is a lowly town crier occupying “el oficio más infame que hay” (“the lowliest job there is”) but rejects money as a reward, craving fame instead!4. his letter opens promising great things (“cosas tan señaladas”) but later he calls it a trifle written in a crude style (nonada que en este grosero estilo escribo”); 5. he affects modesty (no más santo que mis vecinos”) but is proud of his achievement; 6. he is asked to write only about the "matter” but takes it upon himself to give a full account of his life up to that point.

The Prologue ends with Lázaro suggesting that as a hard working man he has achieved more than those who –thanks to the generosity of Fortune-- have “inherited noble estates”- a daring suggestion for the time.

The letter proper is divided into seven sections (“tratados”) of unequal length. Each "tratado" details Lázaro’s experience as he serves, in turn, a blind man (Tratado 1), a priest (Tratado 2), an "escudero" --a very low-born noble (Tratado 3), a friar (Tratado 4), a pardoner i.e. a seller of papal indulgences (Tratado 5), a pedlar and a chaplain (Tratado 6), and a constable (Tratado 7). Of these, the friar, pedlar, chaplain and constable are dismissed in a few lines.

Tratado 1.

In the first “tratado,” Lázaro informs Vuestra Merced that he was born to a miller and his wife on the banks of the River Tormes, in a village close to Salamanca. Lázaro was still a child when his father was killed in a war to which he had been sent after being convicted of ”bleeding” some sacks brought to the mill for grinding. His mother subsequently moved to Salamanca and had a relationship with a black stable man. This relationship ended when the “stepfather” was whipped and basted with hot fat for theft and his mother lashed and ordered not to have further contact with her lover. Unable to care for Lazarillo (the diminutive "–illo" refers to Lázaro as child), his mother handed him over to a blind man to serve as his guide.

Lazarillo quickly and literally learned the hard knocks of life. The first thing the blind man did was tell Lazarillo to put his head close to a stone bull and listen for an unusual sound (the stone bull still stands at one end of the Roman bridge over the River Tormes). Innocently, Lazarillo did as he was told and immediately had his head smashed against the bull by the blind man. It was, as he says, a wake-up call. From then on the relationship between Lazarillo and his master became a battle of wits in which the blind man emerged victorious, with one exception… the final battle!

Lazarillo’s main concern at this stage was survival, i.e. getting enough to eat. But his first master was astute, deceiving not only the child who was blind to the ways of the world, but also adults who should know better. He was a master beggar and knew how to make money, having memorised countless prayers for all occasions. Lazarillo used all the tricks he could to outwit the blind man, stealing from his wine jar, eating more than his share of grapes, replacing a juicy sausage with a turnip, but on each occasion he was found out. In the wine episode, Lazarillo ended up having the wine jar smashed on his face; he didn’t suffer physically after the grape incident but learned a valuable lesson on deception; the sausage incident ended with the blind man stuffing his nose so far down Lazarillo’s throat that Lazarillo threw it up all over his master.

Having suffered enough at the hands of the blind man, Lazarillo determined to move on. The "tratado" ends with one final trick. On a rainy day, as they were crossing a village square, Lazarillo persuaded his master to take a running jump to avoid a wide gutter. The blind man ended up half dead on the ground after crashing into a stone pillar. Lazarillo’s parting words were “Hey, how come you smelled the sausage but not the post? Olé! Olé!” It was Lazarillo’s first clear victory, taking us back at the same time to Lazarillo’s initiation into life with the bull incident. The circle was complete; the blind man had no more to teach him.

Tratado 2.

In the second "tratado," Lazarillo’s met a priest who is the epitome of avarice. Lazarillo’s main concern was still the search for food, but now he faced a formidable all-seeing adversary whose eyes are described as “dancing in their sockets as if they were mercury.” Suffering great hunger while his master had plenty, he thought of running away but was held back because he felt too weak and feared that in fleeing he would be jumping from the frying pan into the fire.

Uusing what he had learnt from his first master, Lazarillo embarked on a battle of wits with the priest centred on his attempts to steal eucharist bread from a chest which the priest kept locked. Lazarillo persuaded a passing tinker to make him a key for the chest, offered him one of the loaves inside as payment and then helped himself to one. When the priest next opened the chest, he suspected that some bread was missing and counted the remaining loaves. Lazarillo then found himself in a quandary: how could he take any bread without the priest noticing it is missing? He started by nibbling morsels hoping that the priest would conclude that mice had got in through the little cracks in the chest. That is what happened, and the priest boarded up the cracks. Lazarillo then drilled a hole in the chest with a knife while his master was asleep. The priest next borrowed a mousetrap and begged some cheese from neighbours, Lazarillo took the cheese and some bread as well. The priest asked the neighbours for advice and one remarked that there used to be a snake in the house. From then on the priest hardly slept, so Lazarillo resorted to raiding the chest during the day, while his master was at church. At night, however, Lazarillo hid the key in his mouth in case the priest should find it. Ironically Lazarillo was eventually uncovered when his breathing caused a whistling sound through the key. The priest believed the sound was made by a snake seeking the warmth of Lazarillo’s body. He smashed at it with a thick stick, and ended up knocking Lazarillo unconscious. When Lazarillo regained consciousness “three days later,” he was unceremoniously dismissed by the priest.

Tratado 3.

By Tratado 3, Lazarillo had arrived in Toledo where he was employed by an “escudero” (squire), one of the best known figures in Spanish literature. When he first met the squire, Lazarillo was impressed by his clothes and general composure and had high hopes that he had landed on his feet. He was quickly disabused, however. The house in which the "escudero" lived had no furniture except a rickety bed, the clothes he wore are all that he had and there was no food! Fortunately, by now Lazarillo had learnt the art of survival so that finding food in the street was no problem. As a result, he did not abandon his new master and in fact ended up feeding him.

Unlike the previous two "tratados," there was no battle of wits in Tratado 3 because the "escudero" was not cruel. He was impoverished, but as a noble (albeit low born) work was beneath him and his honour compelled him to do anything (but work!) to maintain a façade of respectability. As a result, the squire lived in a world of appearances, creating the illusion of well-being when he was in fact destitute. He rented a house and bed he couldn’t pay for; he entertained two “ladies” who ditched him as soon as it became evident that he had nothing to offer them; he left the house each morning with a toothpick in his mouth as if he had crumbs between his teeth when he hadn’t eaten anything. Even when watching Lazarillo eat in the privacy of his house, his pride wouldn’t allow him to ask for a bite. Rather he flattered and wheedled his way into an invitation from Lazarillo to join him: “I tell you, Lázaro, you are the most elegant eater I’ve ever seen… that’s cows foot, is it?… I tell you that’s the tastiest food in the world. I’d prefer that to pheasant any day.”

Towards the end of the "tratado," the squire gave Lazarillo a short version of his life. Brought up somewhere in Old Castile, he left because he did not want to have to take his hat off first to a neighbour of his, even though the neighbour was his social superior. He denies he was poor, claiming that at home he had a few houses which, if they were still standing would be worth a large sum! He also owned a dovecot which would provide him with more than 200 doves a year if it weren’t in ruins! Now if only he could find a titled lord to serve, he would lie, flatter, deceive to remain in his service.

The squire’s fantasies were cut short by the arrival of a man and a woman, owners respectively of the house and the bed. Unable to pay the rental fees for the house and bed, the squire did what he had done each time reality threatened his contrived world: he fled. Left to face the music, Lazarillo was fortunate that some neighbours vouch for him and he was spared imprisonment. He was left to lament on the irony that whereas servants normally abandoned their masters, in his case he had been abandoned by his master!

Tratado 4.

In this very brief "tratado," Lazarillo is introduced to his fourth master, a friar, by some female neighbours he met while living with the squire. In a few words, Lázaro describes the friar as an “enemy” of monastery life, and a lover of worldly activities. He spent so much time visiting people that he wore out more shoes than the rest of his community together. Lazarillo received his first pair of shoes from the friar, but could hardly keep up with him. For that reason and “for other little things which I shan’t mention, I left him.”

Tratado 5.

Lazaro’s fifth master is a pardoner, a seller of papal indulgences, the purchase of which ensured that the buyer’s soul would serve reduced time in Purgatory. The pardoner is described immediately as the most adept and shameless seller of papal indulgencies that Lázaro had ever seen or expected to see. Whenever he arrived at a place, the pardoner would elicit the local priest’s help in getting people to the church by offering bribes in the form of fruit or vegetables. He would spout Latin (or what sounded like Latin) if the priest was uneducated but Castilian if the priest said he knew Latin.

One evening, after a fruitless attempt to get the local villagers to buy indulgences, the pardoner got into an argument with a constable over a game of cards they were playing. The pardoner called the constable a thief; the constable accused the pardoner of being a forger and claimed the indulgences were not genuine. Only the intervention of the townspeople prevented them coming to blows.

On the following day, while the pardoner was preaching the virtues of the indulgences he was interrupted by the constable who claimed that he and the pardoner had intended to dupe the congregation and share the spoils from the sale of the indulgences. At that point the pardoner knelt in the pulpit beseeching God to strike him down if what he was selling was false. On the other hand, if the constable was lying he should be the one punished. Scarcely had the pardoner finished his prayer when the constable fell to the ground howling, with his mouth foaming and face twisted. Only after an indulgence was placed on his head did the constable recover his senses. He then confessed to wanting vengeance for the previous evening and to being in the clutches of the devil who suffered agony at seeing the good that indulgences brought people. Predictably the sales of the indulgences was brisk, not only in that village but in neighbouring villages where news of the miracle spread quickly.

Even Lazarillo was taken in, and only later, when he saw the pardoner and the constable laughing together, did he realize that the whole thing had been planned by his “clever and wily master.” After four months with the pardoner, Lazarillo moved on to his next master.

Tratado 6.

In this short "tratado", the first of the two masters --a kind of pedlar for whom Lazarillo mixed paint-- is dismissed in one line. He is remembered only for causing his servant a lot of suffering. The pedlar is followed by a chaplain who, besides his religious duties, made money on the side renting out concessions to water sellers. He provided Lazarillo with a donkey and pitchers so that he could fetch water from the river and sell it in the streets. This was Lazaro’s first job. The first 30 "maravedís" he earned each day went to the priest, the rest and his takings on Saturdays he kept for himself. During the 4 years he spent on the job Lázaro earned enough to buy himself respectable second hand clothes and an old sword. Seeing himself dressed as an honourable person, he abandoned the job.

Tratado 7.

Lázaro next served a constable but quickly decided that chasing criminals was too dangerous. Thanks to the help of friends, he then found an official job auctioning wine, accompanying criminals on their way to punishment, and as town crier. Lázaro was pleased with what he had achieved, since just about everything dealing with these jobs had to pass through his hands, so he got to make the decisions.

At about this time, Lázaro came to the notice of the Archpriest of St Salvador who proposed he marry a maid of his. Seeing that this could only benefit him, Lázaro agreed. He was very happy with the arrangement even when people suggested that his wife did more than just make the Archpriest’s bed and cook for him. Lázaro was satisfied with the Archpriest’s denial and the assurances that everything he did was for Lázaro’s good. And so the three were happy with the arrangement, and they said no more about the “caso” (only now do we know what the "caso" in the Prologue refers to). And if anyone was about to bring it up, Lázaro simply cut them off and threatened kill them.

English translations:

Alpert, Michael Two Spanish Picaresque Novels: Lazarillo de Tormes and The Swindler Penguin 2003

Applebaum, Stanley Lazarillo de Tormes Dover Dual Language 2001

Garcia Osuna, Alonso Lazarillo de Tormes McFarland and Co. Jefferson NC 2005

Image of Medina del Campo edition from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lazarillo_de-Tormes

Goya's Lazarillo from commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:El_Lazarillo_de_Tormes_de_Goya.jpg

Lazarillo de Tormes is a short but extraordinary work, published anonymously in 1554. It is structured as a letter in which the narrator, Lázaro –a wine taster and town crier in Toledo-- responds to a request made by an unnamed Vuestra Merced (Your Honour). Lázaro has to explain in detail to Vuestra Merced, seemingly his social superior, a certain “caso” (“matter”), the nature of which becomes clear only at the end of the novel/letter.

The book begins with a brief Prologue which is a brilliantly ambiguous: 1. It is written by an ostensibly uneducated town crier but alludes to several classical authors and is full of rhetorical devices; 2. Lázaro wants the letter to come to the attention of many readers and be praised, but it is addressed to one individual; 3. he is a lowly town crier occupying “el oficio más infame que hay” (“the lowliest job there is”) but rejects money as a reward, craving fame instead!

Given that fame is important, it is ironic

that the author did not attach his name to

the work, probably because of the religious

and social satire it contains. The books was

placed on the Inquisition's Index of Prohibited

Books in 1559.

that the author did not attach his name to

the work, probably because of the religious

and social satire it contains. The books was

placed on the Inquisition's Index of Prohibited

Books in 1559.

The Prologue ends with Lázaro suggesting that as a hard working man he has achieved more than those who –thanks to the generosity of Fortune-- have “inherited noble estates”- a daring suggestion for the time.

The letter proper is divided into seven sections (“tratados”) of unequal length. Each "tratado" details Lázaro’s experience as he serves, in turn, a blind man (Tratado 1), a priest (Tratado 2), an "escudero" --a very low-born noble (Tratado 3), a friar (Tratado 4), a pardoner i.e. a seller of papal indulgences (Tratado 5), a pedlar and a chaplain (Tratado 6), and a constable (Tratado 7). Of these, the friar, pedlar, chaplain and constable are dismissed in a few lines.

Tratado 1.

In the first “tratado,” Lázaro informs Vuestra Merced that he was born to a miller and his wife on the banks of the River Tormes, in a village close to Salamanca. Lázaro was still a child when his father was killed in a war to which he had been sent after being convicted of ”bleeding” some sacks brought to the mill for grinding. His mother subsequently moved to Salamanca and had a relationship with a black stable man. This relationship ended when the “stepfather” was whipped and basted with hot fat for theft and his mother lashed and ordered not to have further contact with her lover. Unable to care for Lazarillo (the diminutive "–illo" refers to Lázaro as child), his mother handed him over to a blind man to serve as his guide.

Lazarillo quickly and literally learned the hard knocks of life. The first thing the blind man did was tell Lazarillo to put his head close to a stone bull and listen for an unusual sound (the stone bull still stands at one end of the Roman bridge over the River Tormes). Innocently, Lazarillo did as he was told and immediately had his head smashed against the bull by the blind man. It was, as he says, a wake-up call. From then on the relationship between Lazarillo and his master became a battle of wits in which the blind man emerged victorious, with one exception… the final battle!

Lazarillo’s main concern at this stage was survival, i.e. getting enough to eat. But his first master was astute, deceiving not only the child who was blind to the ways of the world, but also adults who should know better. He was a master beggar and knew how to make money, having memorised countless prayers for all occasions. Lazarillo used all the tricks he could to outwit the blind man, stealing from his wine jar, eating more than his share of grapes, replacing a juicy sausage with a turnip, but on each occasion he was found out. In the wine episode, Lazarillo ended up having the wine jar smashed on his face; he didn’t suffer physically after the grape incident but learned a valuable lesson on deception; the sausage incident ended with the blind man stuffing his nose so far down Lazarillo’s throat that Lazarillo threw it up all over his master.

Having suffered enough at the hands of the blind man, Lazarillo determined to move on. The "tratado" ends with one final trick. On a rainy day, as they were crossing a village square, Lazarillo persuaded his master to take a running jump to avoid a wide gutter. The blind man ended up half dead on the ground after crashing into a stone pillar. Lazarillo’s parting words were “Hey, how come you smelled the sausage but not the post? Olé! Olé!” It was Lazarillo’s first clear victory, taking us back at the same time to Lazarillo’s initiation into life with the bull incident. The circle was complete; the blind man had no more to teach him.

Tratado 2.

In the second "tratado," Lazarillo’s met a priest who is the epitome of avarice. Lazarillo’s main concern was still the search for food, but now he faced a formidable all-seeing adversary whose eyes are described as “dancing in their sockets as if they were mercury.” Suffering great hunger while his master had plenty, he thought of running away but was held back because he felt too weak and feared that in fleeing he would be jumping from the frying pan into the fire.

Uusing what he had learnt from his first master, Lazarillo embarked on a battle of wits with the priest centred on his attempts to steal eucharist bread from a chest which the priest kept locked. Lazarillo persuaded a passing tinker to make him a key for the chest, offered him one of the loaves inside as payment and then helped himself to one. When the priest next opened the chest, he suspected that some bread was missing and counted the remaining loaves. Lazarillo then found himself in a quandary: how could he take any bread without the priest noticing it is missing? He started by nibbling morsels hoping that the priest would conclude that mice had got in through the little cracks in the chest. That is what happened, and the priest boarded up the cracks. Lazarillo then drilled a hole in the chest with a knife while his master was asleep. The priest next borrowed a mousetrap and begged some cheese from neighbours, Lazarillo took the cheese and some bread as well. The priest asked the neighbours for advice and one remarked that there used to be a snake in the house. From then on the priest hardly slept, so Lazarillo resorted to raiding the chest during the day, while his master was at church. At night, however, Lazarillo hid the key in his mouth in case the priest should find it. Ironically Lazarillo was eventually uncovered when his breathing caused a whistling sound through the key. The priest believed the sound was made by a snake seeking the warmth of Lazarillo’s body. He smashed at it with a thick stick, and ended up knocking Lazarillo unconscious. When Lazarillo regained consciousness “three days later,” he was unceremoniously dismissed by the priest.

Tratado 3.

By Tratado 3, Lazarillo had arrived in Toledo where he was employed by an “escudero” (squire), one of the best known figures in Spanish literature. When he first met the squire, Lazarillo was impressed by his clothes and general composure and had high hopes that he had landed on his feet. He was quickly disabused, however. The house in which the "escudero" lived had no furniture except a rickety bed, the clothes he wore are all that he had and there was no food! Fortunately, by now Lazarillo had learnt the art of survival so that finding food in the street was no problem. As a result, he did not abandon his new master and in fact ended up feeding him.

Unlike the previous two "tratados," there was no battle of wits in Tratado 3 because the "escudero" was not cruel. He was impoverished, but as a noble (albeit low born) work was beneath him and his honour compelled him to do anything (but work!) to maintain a façade of respectability. As a result, the squire lived in a world of appearances, creating the illusion of well-being when he was in fact destitute. He rented a house and bed he couldn’t pay for; he entertained two “ladies” who ditched him as soon as it became evident that he had nothing to offer them; he left the house each morning with a toothpick in his mouth as if he had crumbs between his teeth when he hadn’t eaten anything. Even when watching Lazarillo eat in the privacy of his house, his pride wouldn’t allow him to ask for a bite. Rather he flattered and wheedled his way into an invitation from Lazarillo to join him: “I tell you, Lázaro, you are the most elegant eater I’ve ever seen… that’s cows foot, is it?… I tell you that’s the tastiest food in the world. I’d prefer that to pheasant any day.”

Towards the end of the "tratado," the squire gave Lazarillo a short version of his life. Brought up somewhere in Old Castile, he left because he did not want to have to take his hat off first to a neighbour of his, even though the neighbour was his social superior. He denies he was poor, claiming that at home he had a few houses which, if they were still standing would be worth a large sum! He also owned a dovecot which would provide him with more than 200 doves a year if it weren’t in ruins! Now if only he could find a titled lord to serve, he would lie, flatter, deceive to remain in his service.

The squire’s fantasies were cut short by the arrival of a man and a woman, owners respectively of the house and the bed. Unable to pay the rental fees for the house and bed, the squire did what he had done each time reality threatened his contrived world: he fled. Left to face the music, Lazarillo was fortunate that some neighbours vouch for him and he was spared imprisonment. He was left to lament on the irony that whereas servants normally abandoned their masters, in his case he had been abandoned by his master!

Tratado 4.

In this very brief "tratado," Lazarillo is introduced to his fourth master, a friar, by some female neighbours he met while living with the squire. In a few words, Lázaro describes the friar as an “enemy” of monastery life, and a lover of worldly activities. He spent so much time visiting people that he wore out more shoes than the rest of his community together. Lazarillo received his first pair of shoes from the friar, but could hardly keep up with him. For that reason and “for other little things which I shan’t mention, I left him.”

Tratado 5.

Lazaro’s fifth master is a pardoner, a seller of papal indulgences, the purchase of which ensured that the buyer’s soul would serve reduced time in Purgatory. The pardoner is described immediately as the most adept and shameless seller of papal indulgencies that Lázaro had ever seen or expected to see. Whenever he arrived at a place, the pardoner would elicit the local priest’s help in getting people to the church by offering bribes in the form of fruit or vegetables. He would spout Latin (or what sounded like Latin) if the priest was uneducated but Castilian if the priest said he knew Latin.

One evening, after a fruitless attempt to get the local villagers to buy indulgences, the pardoner got into an argument with a constable over a game of cards they were playing. The pardoner called the constable a thief; the constable accused the pardoner of being a forger and claimed the indulgences were not genuine. Only the intervention of the townspeople prevented them coming to blows.

On the following day, while the pardoner was preaching the virtues of the indulgences he was interrupted by the constable who claimed that he and the pardoner had intended to dupe the congregation and share the spoils from the sale of the indulgences. At that point the pardoner knelt in the pulpit beseeching God to strike him down if what he was selling was false. On the other hand, if the constable was lying he should be the one punished. Scarcely had the pardoner finished his prayer when the constable fell to the ground howling, with his mouth foaming and face twisted. Only after an indulgence was placed on his head did the constable recover his senses. He then confessed to wanting vengeance for the previous evening and to being in the clutches of the devil who suffered agony at seeing the good that indulgences brought people. Predictably the sales of the indulgences was brisk, not only in that village but in neighbouring villages where news of the miracle spread quickly.

Even Lazarillo was taken in, and only later, when he saw the pardoner and the constable laughing together, did he realize that the whole thing had been planned by his “clever and wily master.” After four months with the pardoner, Lazarillo moved on to his next master.

Tratado 6.

In this short "tratado", the first of the two masters --a kind of pedlar for whom Lazarillo mixed paint-- is dismissed in one line. He is remembered only for causing his servant a lot of suffering. The pedlar is followed by a chaplain who, besides his religious duties, made money on the side renting out concessions to water sellers. He provided Lazarillo with a donkey and pitchers so that he could fetch water from the river and sell it in the streets. This was Lazaro’s first job. The first 30 "maravedís" he earned each day went to the priest, the rest and his takings on Saturdays he kept for himself. During the 4 years he spent on the job Lázaro earned enough to buy himself respectable second hand clothes and an old sword. Seeing himself dressed as an honourable person, he abandoned the job.

Tratado 7.

Lázaro next served a constable but quickly decided that chasing criminals was too dangerous. Thanks to the help of friends, he then found an official job auctioning wine, accompanying criminals on their way to punishment, and as town crier. Lázaro was pleased with what he had achieved, since just about everything dealing with these jobs had to pass through his hands, so he got to make the decisions.

At about this time, Lázaro came to the notice of the Archpriest of St Salvador who proposed he marry a maid of his. Seeing that this could only benefit him, Lázaro agreed. He was very happy with the arrangement even when people suggested that his wife did more than just make the Archpriest’s bed and cook for him. Lázaro was satisfied with the Archpriest’s denial and the assurances that everything he did was for Lázaro’s good. And so the three were happy with the arrangement, and they said no more about the “caso” (only now do we know what the "caso" in the Prologue refers to). And if anyone was about to bring it up, Lázaro simply cut them off and threatened kill them.

English translations:

Alpert, Michael Two Spanish Picaresque Novels: Lazarillo de Tormes and The Swindler Penguin 2003

Applebaum, Stanley Lazarillo de Tormes Dover Dual Language 2001

Garcia Osuna, Alonso Lazarillo de Tormes McFarland and Co. Jefferson NC 2005

Image of Medina del Campo edition from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lazarillo_de-Tormes

Goya's Lazarillo from commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:El_Lazarillo_de_Tormes_de_Goya.jpg